We have known that the lifestyle of an average citizen from a high-income country contributes significantly to the global climate crisis, but how and by how much? What would it take to align these lifestyle emissions with the Paris Agreement? Our new report focuses on answering these questions in Norway by applying the lifestyles carbon footprint approach developed in our work on 1.5-degree lifestyles.

Our analysis of consumption and lifestyles impacts in Norway, as is the case with similar high-income countries, shows that reducing the footprint in line with the Paris Agreement requires major changes in the high impact domains of personal transport and nutrition, which account for more that two-thirds of lifestyle carbon footprints, and also in housing, consumer goods, leisure and services.

It is clear that such deep systemic changes cannot be achieved by individuals consumers acting alone. Lifestyles are shaped by social norms and expectations, the economic system, and the technical infrastructure surrounding us. Collective decisions and innovative public policies are essential to achieve the needed systemic transformation.

What does the Norwegian lifestyle carbon footprint look like?

Our new report is the result of a fruitful partnership with Framtiden i våre hender (Future in Our Hands) – one of Norway’s largest environmental NGOs. It was launched on 25 April as part of their 50th anniversary.

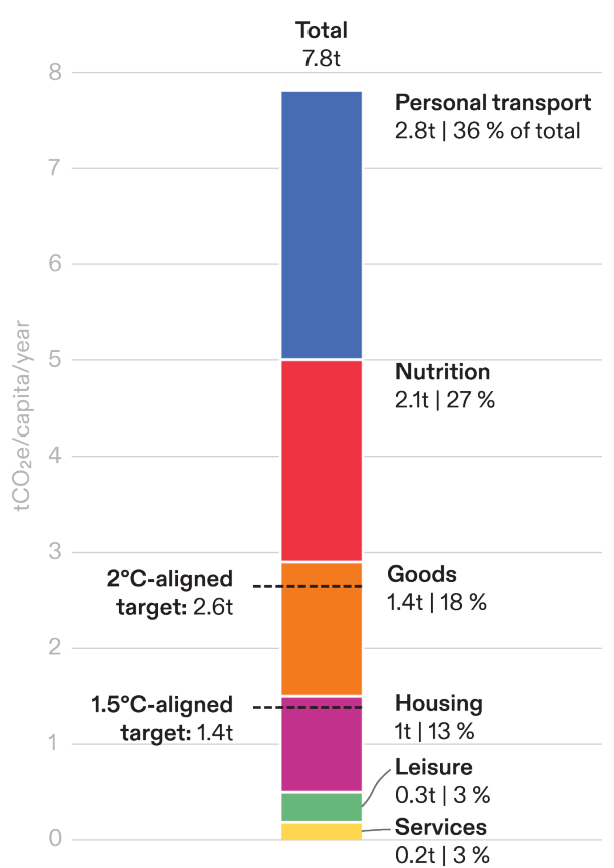

Norway’s average lifestyle carbon footprint is estimated at 7.8 tonnes of CO2 equivalent (tCO2e) per capita per year (see the Figure below). Nearly two-thirds of this footprint is related to just two lifestyle domains: personal transport (36%, or 2.8 tCO2e/capita/year) and nutrition (27%, or 2.1 tCO2e/capita/year).

Flying and car transport contribute almost equal shares of the transport footprint. This reflects the fact that Norwegians fly much more than the global average. In addition although around 20% of cars on the road are electric, the sheer demand for car travel and the long distances travelled per person cancel out the benefits gained through electrification. The impact of nutrition is dominated by meat and dairy products.

Smaller contributions are from consumer goods (18%, or 1.4 tCO2e/capita/year) and housing (13%, or 1.0 tCO2e/capita/year). The low emissions from housing energy use are partly due to the country’s abundant hydropower resources and the resulting low-carbon power mix.

The study also looks at how the average footprint could be reduced and identifies the following high-impact options for change:

- Reduce meat consumption. Diets with less meat, especially red meat offer a potential reduction of 640 – 1200 kgCO2e. Adopting a completely plant-based diet clearly offers the greatest reduction results but shifting to a vegetarian diet (including dairy products and eggs) also results in substantial reductions.

- Reduce air travel. Reducing international flying or shifting to train travel can offer emissions reductions between 750 – 1130 kgCO2e. For the minority of people who fly abroad privately several times per year, travelling less often or opting for train travel instead of flying can shrink the footprint even more than for the average person.

- Reduce consumption. Reduced purchasing of new consumer goods, together with a deep decarbonisation of the production system (each with a potential of 690 kgCO2e).

- Switch from fossil fuel-based cars to electric vehicles. This impact option focuses on climate-smart personal car travel. Switching from fossil fuel-based cars to electric vehicles has the potential to reduce up to 560 kgCO2e.

An additional assessment of a fictive high-consumption lifestyle, assumed to be common among well-off Norwegians, shows that the lifestyles footprints could easily be twice as high as for the average Norwegian. Targeting these lifestyle patterns specifically can greatly reduce overall emissions. This is not only a matter of fairness and of gaining public acceptance for climate policies, but equally a matter of policy effectiveness. To make average emissions fall as needed, the disparity between high-emitters and low-emitters must be reduced.

A path forward for Norway

The study provides high-level direction for policy, offering ideas and inspiration for various policy actions to reduce emissions and promote sustainable lifestyles including the following:

- A new national vision for Norway, centred on wellbeing, which shows what a fully decarbonised advanced welfare society could look like in the 21st century, and what role it should play in the world.

- Policy packages targeting lifestyle areas with high climate impact, based on a choice editing approach. Choice editing is a three-pronged approach where policy makers edit out options for carbon-intensive lifestyles and consumption and edit in more desirable alternatives by making them more easily available, affordable, and attractive.

- City initiatives that encourage and enable low-carbon living, such as zoning regulations promoting proximity and diversity, additional taxes on large newly built single-family homes, and demonstration projects on the repurposing of existing buildings.

- Strengthened support to low-income countries, enabling them to leapfrog to low-carbon infrastructure and strengthen climate resilience.

- Improved statistics on consumption and lifestyles along with improved analytical tools for understanding how Norwegian’s ways of living impact the living planet. The country should also consider setting time-bound targets for its consumption-based carbon footprint to complememt existing targets for domestic emissions.