City Background

As the main financial, corporate and commercial centre in South America, São Paulo is the most influential Brazilian city and the most populous one. The city faces enormous challenges in different areas. In the mobility sector, subway and train lines are not enough to attend the population’s needs for commuting, bicycle paths are very scarce and not often provide the security needed for cyclists and the car traffic is very intense. Regarding food consumption, citizens are over consuming high-calorie foods (with high sugar and fat content) and are under consuming fruits and vegetables, despite the alarming hunger situation of millions of people.

When it comes to climate change, in 2020 the Municipality of São Paulo launched the Climate Action Plan 2020-2050 (PlanClimSP), an initiative that demonstrates how the city of São Paulo will align its actions with the commitments of the Paris Agreement, envisioning a zero-carbon city in 2050. In this vein, the Future Lifestyles Project identifies, based on participatory process and citizens engagement, pathways for reducing lifestyle carbon footprints across the domains of housing, mobility, food, consumer goods, services and leisure. The aim of the project is to characterise the lifestyles of citizens of São Paulo, their interests and barriers regarding low carbon lifestyle options and assessing the feasibility of these options. Furthermore, the project aims at identifying supporting measures to enable low carbon lifestyle options implementation, creating a city vision for 2030.

Current carbon footprint and 2030 projection

In São Paulo, the total annual emission is of 3.6 tCO2e per capita, and the consumption categories that contribute the most to these emissions are food (38%), mobility (27%) and housing (23%).

The participatory process consisted of two online workshops and a household experiment, where 32 different lifestyle options were presented to the participants, in order to understand their feasibility considering diverse contexts.

The following options showed the highest adoption rates:

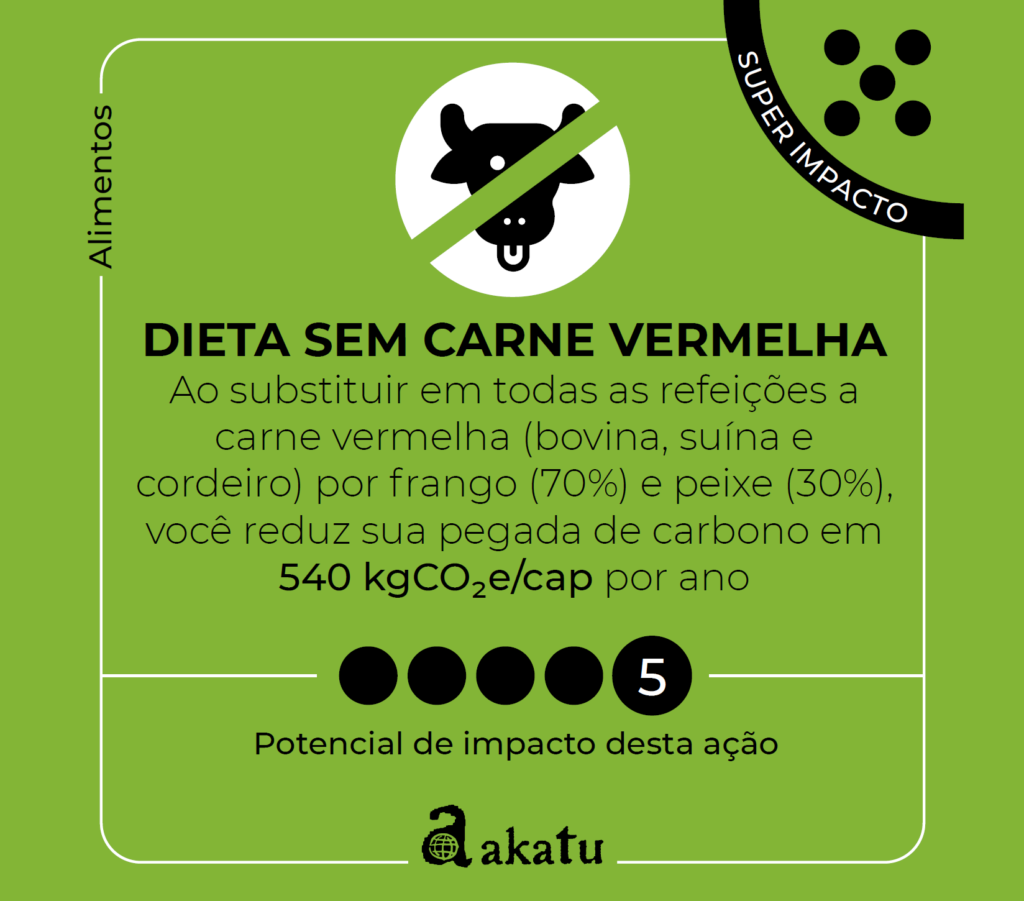

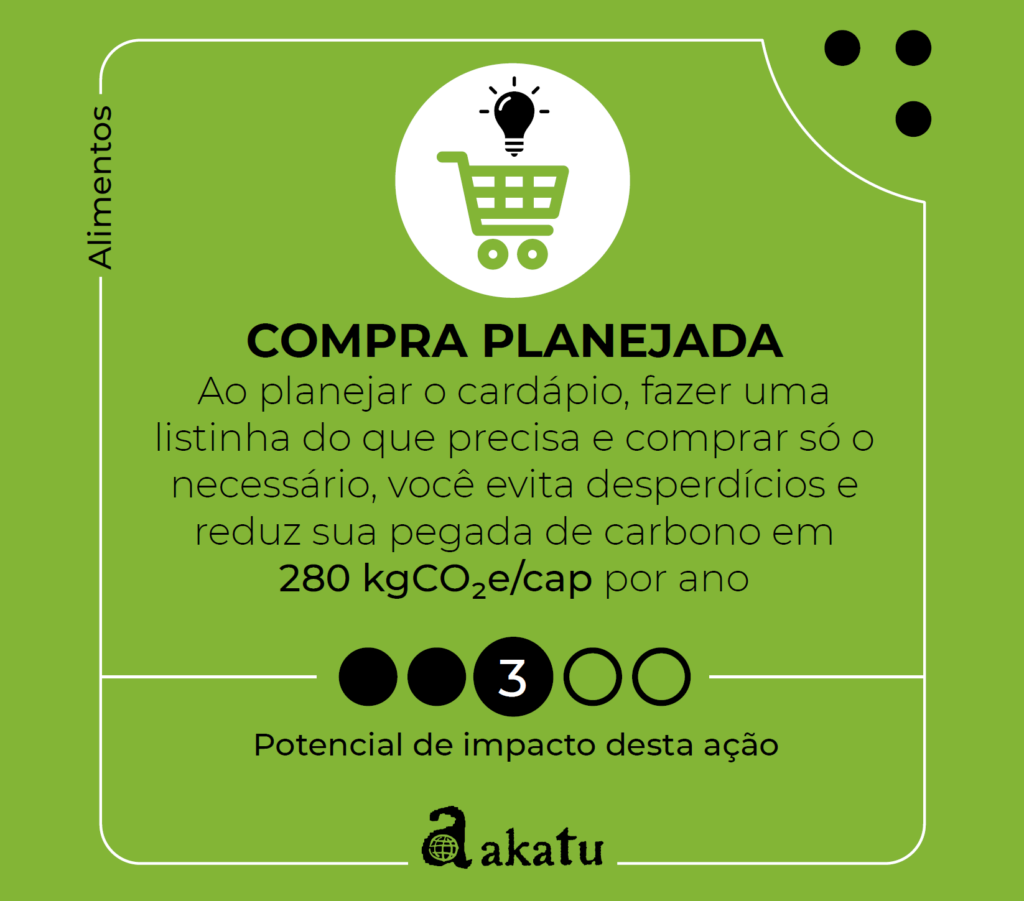

- Food: low-carbon protein instead of red meat (75%), plan food shopping to avoid waste (88%);

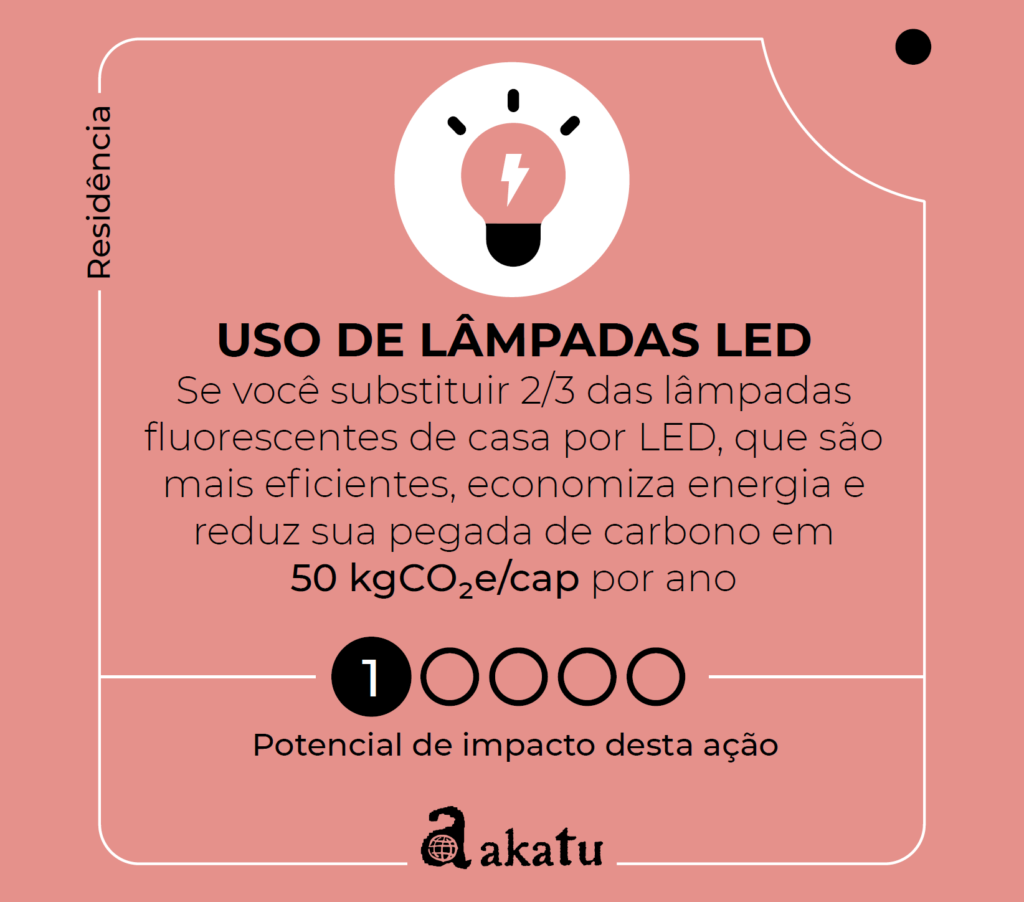

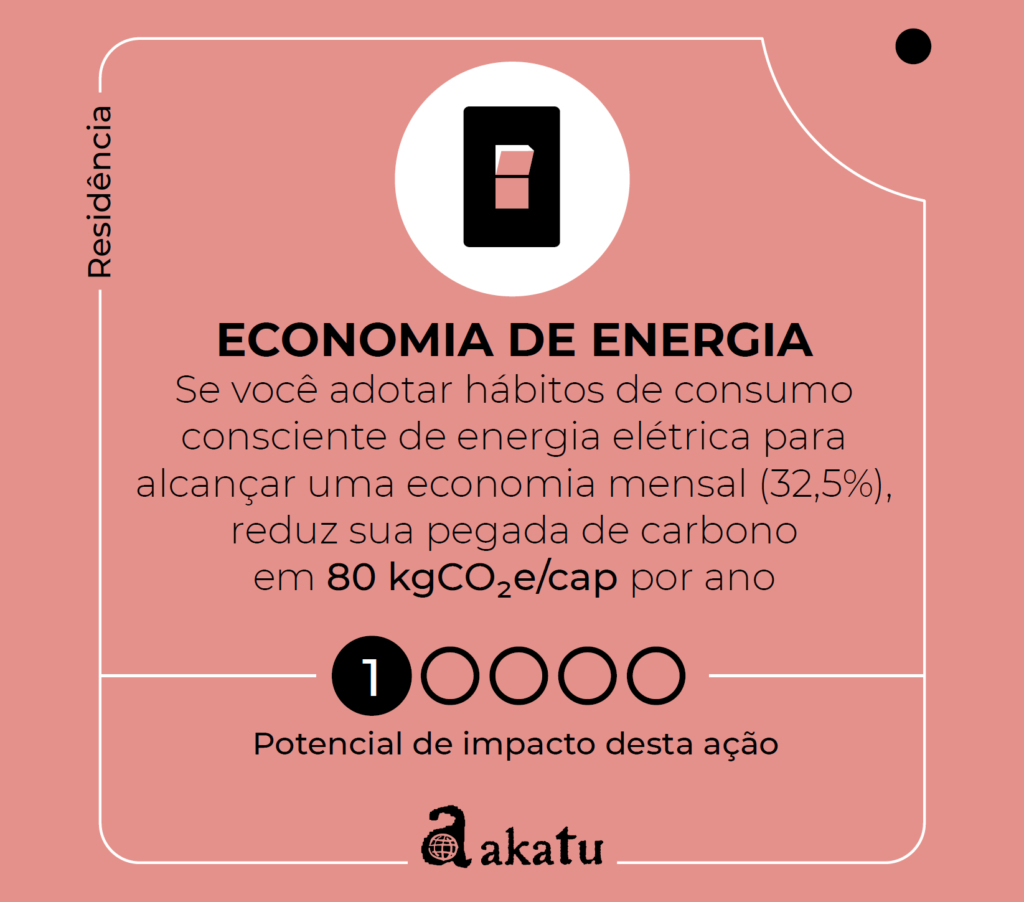

- Housing: reduce home electricity use (88%), and switch to LED lightning (75%);

- Mobility: using public transport (63%), and home office (63%);

- Goods: reduction in electronics consumption (75%), and longer lasting clothes (63%).

Lifestyle Option cards: Instituto Akatu (Option Catalogue)

If fully implemented, such options have the potential to reduce the annual carbon footprint of a citizen from 3.6 to 1.5 tCO2e (almost 60% reduction), achieving the 2.5 tCO2e goal set for 2030 (Figure 1).

Food is both the category with the highest current carbon footprint and the one where most intense reductions are possible. Considerable reductions are also possible with regard to housing, while mobility shows lower reduction potential. Regarding goods consumption, the reduction projected is more modest, while for leisure and services there are no changes in carbon footprint.

Along with the direct benefits of emissions reduction, multiple co-benefits come with adopting low carbon lifestyles, including:

- Reduction of city pollution, especially air pollution, due to changes in mobility;

- Better community relationships, through adopting collaborative modes of consumption, such as re-selling or donating overproduced food otherwise destined to waste;

- Financial benefits (in terms of cost savings) resulting from food waste reduction, energy and water saving, and house sharing.

Key Points

Overall, participants of the workshops agreed on a few elements that describe a “desired city” of São Paulo and that highlight where further investments and improvements are needed: better infrastructure (especially mobility infrastructure), expanding recycling systems and collaboration among stakeholders (such as governments, companies, NGOs and civil society). Furthermore, the participants envisioned a more united society in the future, where each one has its own role to play, as a citizen, a company, an NGO, a government, and others players, emphasizing that it is critical for all to address common challenges in an inclusive way.

Recommendations

Some challenges were identified across domains, meaning that they were not unique to only one category. Below, a few examples of these challenges, and suggested supporting measures that main stakeholders could provide: government, companies and civil society.

| Challenges | Opportunities / Roles of stakeholders | ||

| Governments | Companies | Civil Society | |

| Lack of access (e.g., buy more durable clothes; use of public transport) | Investment in urban mobility infrastructures and implement more ambitious mobility policies | Provide technologies for improving access | Identify lack of access and cooperate with citizens and local businesses |

| Lack of information/ knowledge (e.g., buy more durable clothes; purchase food that would otherwise be thrown away) | Laws that demand transparency and information provision from companies | Provide complete and transparent information on goods and services | Demand information from governments and companies |

| Lack of infrastructure (e.g., poor condition of Brazilian roads; use of public transport; cycling) | Develop infrastructures for alternative mobility options and implementing national and local policies

|

Support infrastructure development

|

Demand improvements based on the services used |