By Saamah Abdallah, Magnus Bengtsson, Lewis Akenji (Hot or Cool Institute) and Mathieu Saujot, Clémence Nasr, Marion Bet (IDDRI)

The “21st Century Eco-Social Contract” project is being carried out with contributions from F-X. Demoures (Grand Récit), L. Francou (Parlons Climat), S. Dubuisson-Quellier (CNRS- SciencesPo), M. Fleurbaey (Paris School of Economics), C. Lejeune (SciencesPo), J. Ferrando (Missions Publiques), L. Chancel (SciencesPo – PSE), S. Thiriot (Ademe)

Read this blog in French on the IDDRI website.

—

Sustainable wellbeing seems possible…

We largely know what a sustainable society could look like. It involves the complete decarbonisation of our energy systems. It requires the expansion of sustainable farming practices such as agroecology coupled with changing diets. We will consume and produce less. The private vehicle – be it powered with the internal combustion engine, hydrogen or an electric battery – would become much less dominant compared to other modes of transport. Sufficiency would become a social norm for consumption in all sectors, enabling us to reduce our footprint while providing the necessary wellbeing within planetary boundaries. Inequality would be reduced – not just to eliminate poverty, but to prevent the unsustainable overconsumption of the rich. These are the kinds of solutions that think tank and sustainability experts are forming a consensus on (e.g. the Hot or Cool Institute, IDDRI, Konzeptwerk Neue Ökonomie, Wellbeing Economy Coalition, Enough is Enough).

… and yet out of reach

And yet, although these visions are technologically feasible, and can provide the basis for everyone’s wellbeing, they are often portrayed as naïve, utopian and out of reach. In part, this is due to our lack of knowledge of the social and political path that would lead to such a society, and because many existing social conflicts and tensions make the existence of such a path seem unlikely today. In the absence of a credible path, we are told to carry on with the same unsustainable lifestyles and economic system as before, and that somehow technology will solve our problems. But, as the science makes painfully clear, this is a very risky bet. As a result, despite clear solutions in reach, humanity seems to be walking off a cliff face.

Political challenges

While there are many contributing factors behind this deadlock, politics seems to be at the heart of the problem. Vested interests that hold disproportionate political power. Short-term electoral cycles that discourage policies where the benefits cannot be seen within four or five years. Political systems that encourage polarisation and posturing. And hegemonic ideas and assumptions about how the economy works and the appropriate role of governments that discourage bold policy action and mission-driven innovation. Many politicians seem to understand the need for radical action, but see little incentive to be bold, and every reason to avoid the possible backlash.

That lack of will and fear of change is understandable. Often, when tentative attempts have been made to address climate change, they have been met with harsh opposition – from the Gilet Jaunes in France, to the farmer protests in the Netherlands – resulting as much from existing inequalities and perceived injustices as from the expected consequences of these decisions. Large segments of society have felt that freedoms or ways of life that they have understandably taken for granted are being attacked. For the working classes this is seen as an additional injustice to their already constrained lifestyles. This reaction has been especially acute when policies have been perceived to affect ‘ordinary’ people the most, and when they are seen to be imposed top-down by elites. Things could have turned out differently if there had been a collective discussion on our model of society and the institution needed to support it.

Meanwhile, anti-climate change politics has become an integral part of populism (e.g. the AfD in Germany, Vox in Spain or Donald Trump). And the ‘the people vs. the elite’ mindset has been fuelled by a system that seems rigged in favour of the wealthy. With deep mistrust in politicians and the elite they are seen to represent, many voters will not accept bold policies of any kind, as was witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

With that in mind, what pathways to sustainable wellbeing might exist? We need a dramatic shake-up of the political system, and it can’t be elite-driven. But does that need to entail a full-scale revolution? Another storming of the Bastille?

Not necessarily. The Hot or Cool Institute and IDDRI are part of a growing group of organisations exploring a milder form of revolution, one that is built around the transformation of our social contract. We are not expecting this to be a magic button that will teleport us into a utopian future. But we do believe that a new social contract could be an integral part of building better societies. Furthermore, a reflective co-creation process can help both political actors and the public to break free from unconscious assumptions about how society ‘has to’ work, as well as help us diagnose and understand the problems we are facing now.

The social contract: an idea with long roots

The idea of a social contract emerged during the Enlightenment as an idealised hypothetical agreement between the ruled and the ruler. It legitimised state power without recourse to some sort of divine order. For political philosophers of the age, such as Hobbes and Locke, the idea helped understand how it was in people’s interests to submit to a political sovereign that maintained law and order, despite a loss of some freedoms. Rousseau, who emphasised the importance of individual freedom, also acknowledged that rulers are needed to manage society, but stressed the need for them to be democratically selected. The supposed breakdown of a social contract was the premise of the US Declaration of Independence in 1776, which effectively argued that British rule in the colonies was no longer legitimate because it did not contribute to people’s unalienable rights to “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness”.

An evolving concept

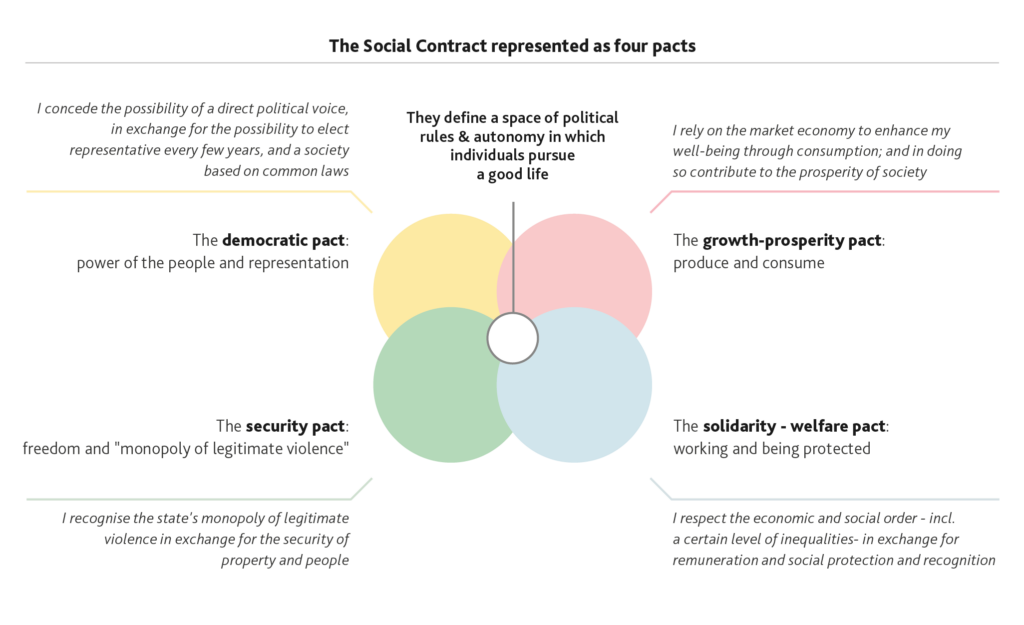

Initially for Hobbes, the social contract was about guaranteeing physical security, and protected individuals against the violent primaeval state of nature. Over the years, the implicit social contract has evolved. The American founding fathers introduced a pact related to representative democracy – in most countries we accept that our political power is mostly transferred to the representatives we vote for, rather than being exercised by the citizens themselves. Referendums are the rare occasion where, in some countries, we can express our opinions on a political issue directly.

Industrialisation and the post-war area saw the emergence of welfare pacts – whereby the rise of a wage labour economy (i.e. that most people became dependent on wages from capitalists for their income) was followed by the development of a safety net provided by the state. One can also talk of a growth-prosperity pact around affluent consumption, whereby citizens are expected to seek to enhance their wellbeing through consumption in the market economy, thereby contributing to economic growth, which, in turn, will create jobs.

Social contracts have been implicit…

These pacts (and possibly others), however, have mostly been implicit. Citizens rarely get to sign a social contract, let alone contribute to its drafting. In many cases, the social contract is implied, or only partly covered through the definition of individual rights and government powers in a constitution (for example the US Bill of Rights), written by elected representatives (i.e. the rulers). There are many examples of constitutions which have been approved by referendum (from Iceland in 1944, to Ecuador in 2008 and Kenya in 2010), but these constitutions tend to be written by the politicians, and citizens are simply given a binary yes or no choice. In other cases, citizens have had no say.

… and they are not being fulfilled

The development of social contracts has generally been erratic, organic and often the result of prolonged conflict. For example, women were allowed to enter the democratic pact and given suffrage only after sometimes violent struggles. The emergence of the welfare state was a complicated process which partly resulted from greater solidarity within countries during and after the two world wars, but also a fear amongst elites of the rise of communism.

Now, in the face of multiple crises, polarisation and conflict is reemerging in the old democracies of Europe and North America, not to mention in other parts of the world. In many ways, it seems our social contracts are not being fulfilled. Electorates do not feel represented by mainstream political parties and increasingly turn to ‘protest’ parties which claim to speak for ‘the people’. For many workers, work is no longer a source of emancipation and dignity. The welfare state and healthcare systems are increasingly suffering, and punitive and inappropriate management methods are being introduced in some countries. Economic prosperity, as measured in terms of median incomes, has not risen with GDP growth, and is even forecast to decline in some countries. Low-earning households have seen their spending power decline and the quality of public services deteriorate. Meanwhile, a small economic elite has become enormously wealthy. Perhaps most fundamentally, governments are not even fulfilling the basic Hobbesian security pact, in that they are failing to protect citizens against the devastating impacts of climate chaos and to organise our adaptation and disaster preparedness. Like the British colonial overlords of North America in the 18th century, states today appear to be failing to meet their basic duty to protect citizens.

Time for a new eco-social contract

To protect citizens, states need to reduce our environmental impact, including by changing our food, mobility and consumption practices. But our current social contract, which is partly based on the promise of ever-growing opportunities for consumption, makes it hard to even contemplate such policies. That is why we need a new one. Co-creating a new contract would provide the opportunity to discuss the freedoms we value most in the context of the climate crisis . It would allow us to reassess the place of consumption in relation to our rights as citizens and workers and what we are willing to exchange for the possibility of limiting the risks to our security posed by the ecological crisis. By considering the multiple pacts of our social contract together, and how they can be redefined with fairness for all borne in mind, this should help ensure that climate protection policies are met with more public acceptance.

It would allow us to overcome the timidity of our politicians and the short-termism of our electoral cycles. It would put ordinary citizens on the same table and on equal terms with vested interests. It’s time to put the reciprocal responsibilities behind these four pacts back on the table for discussion, to find the conditions for shared change. A deliberative process, involving a representative group of citizens, could make this the first time that the philosophical concept of the social contract is actually made into a literal reality (Chile’s 2022 constitution would have been a powerful example had it been approved). Given that in most Western countries, the common understanding of what the social contracts entail reflects what the world looked like in the 1950s, the process seems long overdue.

Our project

Hot or Cool and IDDRI are not the first organisations to propose this: parts of the UN, Green Economy Coalition, Friends of Europe, the European Trade Union Institute and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre have all argued for the need for a new social contract that can accommodate ecological realities (not to mention other challenges such as demographic changes and digitalisation), and some of these organisations have stressed the need for bottom-up processes. But there are many questions that still need to be answered before this is possible.

- Firstly, how have our modern social contracts emerged? We will consider two countries – France and the UK – with different historical trajectories. In doing so, we expect to find that the social contracts we currently take for granted are neither immutable nor inevitable.

- Secondly, do citizens really ascribe to some form of implicit social contract? If so, what are their expectations in terms of rights, duties, roles, and mechanisms for accountability? What are the unfulfilled promises ? And are there important differences between demographic groups that need to be acknowledged?

- Thirdly, are governments upholding the contract? The general perception is that they are not doing so well, but does the data demonstrate this? To test this, based on how experts and citizens define the social contract, we will develop a dashboard of indicators that measure European governments’ fulfilment of their side of the deal.

- Lastly, how can citizens engage in the complex process of renewing the social contract? We will work with participation and deliberation experts to explore potential approaches, with a view to inspiring governments to rise to the challenge and support such a process in the near future.

Most people in the public worry about climate change, and say that they are willing to change their lifestyles in order to mitigate its impact. But their willingness to actually make such changes, depends strongly on whether this is done in a way that feels fair, coordinated, and effective. A bottom-up deliberative process to develop a new social contract would give the public the confidence that we as societies are working together to address the challenge, and the confidence for politicians to make bold decisions. And that’s really all we need.

Find out more about the project here.